Origin of the Undertaking—The First Competition, November 1829—Description of Mr. Brunel’s Plans

After Mr. Brunel had recovered from his accident in the Thames Tunnel, he went for a trip to Plymouth, where he examined with great interest the Breakwater and other engineering works in the neighbourhood. He notes in his diary that he went to Saltash, and that he thought the river there ‘much too wide to be worth having a bridge.’ This remark was no doubt made in consequence of his father having some years before been consulted as to the construction of a suspension bridge at this place, which Mr. Brunel himself, eighteen years afterwards, selected for the crossing of the Tamar by the Cornwall Railway, and built there the largest and most remarkable of his bridges.

For the remainder of the year 1828, and during the greater part of 1829, Mr. Brunel kept himself fully employed in scientific researches, and in intercourse with Mr. Babbage, Mr. Faraday, and other friends; but he was without any regular occupation, until, in the autumn of 1829, he heard that designs were required for a suspension bridge over the Avon at Bristol, and he determined to compete.

This project originated in a bequest made in 1753, by Alderman William Vick, of the sum of 1,000£ to be placed in the hands of the Society of Merchant Venturers of Bristol, with directions that it should accumulate at compound interest until it reached 10,000£, when it was to be expended in the erection of a stone bridge over the river Avon, from Clifton Down to Leigh Down. Alderman Vick stated that he had heard and believed that the building of such a bridge was practicable, and might be completed for less than 10,000£

The legacy was duly paid to the Society of Merchant Venturers, and invested by them. The interest accumulated; and in 1829, when the fund amounted to nearly 8,000£, a committee was appointed to consider in what way it would be possible to carry out Alderman Vick’s intentions.

An estimate for a stone bridge was procured, but as it gave the cost at 90,000£, it was evident that this scheme must be abandoned.

The committee then advertised for designs for a suspension bridge. Mr. Brunel, on hearing through a friend of the proposed competition, went to Bristol; and, after examining the locality, he selected four different points within the limits prescribed by the instructions of the committee, and made a separate design for each of them. His plans were sent in on the day appointed, Nov. 19, 1829, with a long statement, from which the following description of them is taken.

The first design was for a bridge of 760 feet span between the points of suspension, the length of the suspended floor being 720 feet. In order to obtain a height of 215 feet above high-water mark (which was the least that the levels allowed of), towers 70 feet high would have had to be built on the cliffs to carry the chains. The total length of chain, including the land-ties, was about 1,620 feet. Mr. Brunel did not approve of this design, as the situation was not favourable to architectural effect, a point to which the committee attached great importance; but he suggested it from its being somewhat more economical in construction than his other plans.

In another design, the situation being some way farther down the river than that of the design last mentioned, towers would also have been necessary. The distance between the points of suspension was 1,180 feet, with a suspended floor of over 900 feet. It is probable that Mr. Brunel only proposed this plan because the site came within the limits of deviation, as he does not say anything in favour of it in his report.

The two remaining plans are the most interesting of the series, as there can be no doubt that, if Mr. Brunel had had his own way, he would have adopted one of them for execution; and it appears from a little sketch on the top of one of his earliest letters from Bristol, that his first idea for the bridge was that which is carried out in these two designs. The site selected was one where the rocks rise perpendicularly for a considerable height above the proposed level of the bridge, and therefore piers and land-ties were dispensed with, the chains being hung directly from the rock. No masonry was required except for architectural effect.[1]

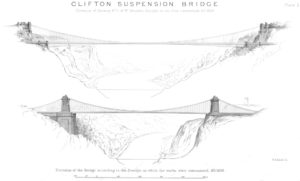

Plate I.

CLIFTON SUSPENSION BRIDGE.

Elevation of Drawing Nº 3 of Mr. Brunel’s Designs in the first competition. AD. 1829

Elevation of the Bridge according to the Design on which the works were commenced. AD. 1836.

The principal difference between these two designs is that in the second a short tunnel is avoided at one end. The style of architecture selected for the tunnel-front and the face of the rock, as shown on the drawings sent in to the committee, is Norman. There are also extant many beautiful sketches made by Mr. Brunel for different parts of the design. [2]

In determining upon the mode of construction, which was the same in the four designs, Mr. Brunel acted upon the principle which guided him in all his subsequent undertakings, which was, as he states in his report, ‘to make use of all that has been found good in similar works, and to avail himself of the experience gained in them, and to combine with all their advantages the precautions which time and experience had pointed out.’

He dismissed in a few words the plan of breaking the span into two or three lengths. This was in his opinion unnecessary, and he computed that the cost of a pier built up from the water’s edge to sufficient height above the bridge to carry the chains, would be at least 10,000£ For this reason he recommended the adoption of spans, the smallest of which far exceeded any up to that time constructed.

In designing the chains, he dispensed with the short connecting links, which had been previously adopted in suspension bridges, introducing instead the method now universally used, of connecting each set of links directly with the adjoining one by means of a pin passed through the holes of both. The number of joints and pins was thus reduced one half, and a considerable saving of expense, as well as diminution of weight, effected.

Another improvement, which diminished still further the weight of the chains, was making the links in lengths of 16 feet, or nearly double that of the longest links at the Menai bridge. The chief reason for this alteration was to ensure a near approximation to equality in the strains on the different links, should all the distances between the holes not be exactly equal. This improvement was afterwards carried still further in the Hungerford Suspension Bridge, the links of which were 24 feet long. [3]

Mr. Brunel also intended to introduce equalising beams in the supports of the floor, so that each chain should bear an equal share of the load. By this arrangement, there would have been comparatively few points of suspension, and ‘the view of the scenery would not be impeded from the observer being surrounded by a forest of suspension rods.’

The disturbance of the strains on the links arising from the greater expansion of the metal of the outer links by the direct heat of the sun, he proposed to obviate by sheet-iron plates placed on each side of the chains, but separated from them by a small interval, and thus screening them from the heat. He did not, however, use this protecting covering at the Hungerford bridge.

All the designs show a camber or rise in the centre of the platform of the bridge, to the extent of two or three feet; and the main chains are brought down almost to the level of the platform. To this last arrangement, as tending to prevent undulation, Mr. Brunel attached some importance; and he further intended to stiffen the bridge against the action of high winds by a system of transverse bracing, and by the addition of inverted chains, similar to those used with success by his father in the Bourbon bridges.[4]

Such, then, were the main features of the bold and carefully matured designs placed by Mr. Brunel before the committee. Out of twenty-two plans submitted, only those of Mr. Brunel and four other competitors were deemed worthy of consideration. He and his friends were naturally much gratified at this, and were full of hope for his ultimate victory. But now, when he seemed to have a fair chance of success in a contest which he justly deemed would have a most important bearing upon his future professional career, an obstacle presented itself, which for the time seemed almost insurmountable; for he met with an unexpected opponent in Mr. Telford, the foremost engineer of the day, and the designer of the famous suspension bridge over the Menai Straits.

[1] The dimensions of these designs were as follows:—

(a.) Length of floor 890 feet. Distance between points of suspension 980 ” Length of chain 1,300 ” With a capacity to bear excessive load of 650 tons. (b.) Length of floor 916 feet. Distance between points of suspension 1,160 ” Length of chain 1,468 ” With capacity to bear excessive load of 650 tons.

| (a.) | Length of floor | 890 | feet. |

| Distance between points of suspension | 980 | “ | |

| Length of chain | 1,300 | “ | |

| With a capacity to bear excessive load of | 650 | tons. | |

| (b.) | Length of floor | 916 | feet. |

| Distance between points of suspension | 1,160 | “ | |

| Length of chain | 1,468 | “ | |

| With capacity to bear excessive load of | 650 | tons. |